Authorities in Pakistan say at least 124 Pakistanis were on a boat that sank off Greece with hundreds feared drowned.

By Abid Hussain

*First Published on Al Jazeera

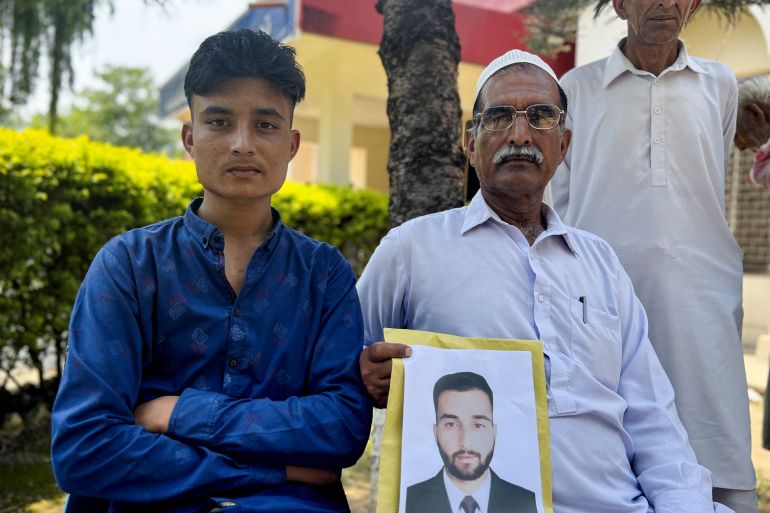

Islamabad, Pakistan – Two of Abid Kashmiri’s family members were on board the refugee-filled vessel that capsized off the coast of Greece last week.

A cousin, Imran Nazir, and nephew, Abdul Islam, travelled from Kotli district in Pakistan-administered Kashmir to Libya in March after securing valid visas for the war-torn country.

But Libya was not to be the pair’s last stop, said Kashmiri, adding that his family knew their real destination: Europe.

“There are many people from our village who have managed to leave for European countries where they are now settled, allowing their families here in Pakistan to live well,” Kashmiri, an electrician, told Al Jazeera on Tuesday.

Family members had paid 2.2 million Pakistani rupees ($7,655) for each of the travellers to “agents” who provide documentation for people looking to find financial opportunities abroad, he said.

“Both Nazir and Islam were unmarried and they, too, wanted to find their way to Europe,” he added.

They are now considered among the hundreds missing from the Greek boat tragedy.

The International Organization for Migration (IOM) and the United Nations refugee agency (UNHCR) have said that between 400 and 750 people were believed to have been on board the boat that capsized on June 14 in the Ionian Sea some 47 nautical miles (87km) off the Greek town of Pylos.

So far, only 104 survivors have been found alive. None of the women or children who were allegedly kept in the hold of the boat have been found.

‘He was a good kid and a good student’

According to data compiled by Pakistan’s Federal Investigation Agency (FIA), at least 124 people from Pakistan have been identified so far as being on board the boat. Only 12 of them reportedly survived. Media reports, however, put the number of Pakistanis on the boat to be around 300.

The tragedy off Greece was the third major incident recorded since February in which migrants and refugees from Pakistan lost their lives at sea.

In February, more than 20 Pakistanis were among 60 who died when a boat capsized near the southern Italian region of Calabria. Two months later, Pakistanis were among the 57 bodies that washed ashore in Libya after two boats carrying refugees capsized in the Mediterranean Sea.

Anis Majeed, a 24-year-old law student from the Kotli district, said that his cousin Awais Asif was also one of the people on board the boat that sank last week.

“My cousin had left the country five months ago and when he was departing, hundreds of people came to bid him farewell,” Majeed told Al Jazeera.

According to Majeed, the 21-year-old Asif made the dangerous journey because of his family’s poor financial situation and his father’s deteriorating health.

“He was a good kid and a good student. But he decided to take this journey for greener pastures and a better financial future for himself and his family,” Majeed said.

“There are so many people in our area who have managed to change their life by travelling to Europe, my cousin thought he could do the same, too.”

‘Crime of consent’

Rana Abdul Jabbar, a senior official with the FIA, said that 90 percent of the people they have identified as being on board the boat that capsized had travelled legally to Libya first.

“According to our records, a vast majority among these people got either a work permit or a travel visa to Libya, and they flew there from Karachi via Dubai, for which they paid money to agents who facilitated their paperwork,” he said, adding that authorities had apprehended 26 alleged human traffickers involved in smuggling people on board the capsized boat.

In 2022, the FIA prevented 19,000 people from leaving Pakistan through land or air routes, Jabbar said, while 10,000 people have been intercepted so far this year.

He said more than 34,000 people from Pakistan were deported from various European countries in 2022 for staying without documents.

Previously, he said, most of the Pakistani people trying to reach Europe used to take land routes, which involved travelling through Iran, Turkey and Greece.

“Since many of these countries, including Pakistan, have deployed stricter border control policies, migrants have now switched to taking [the] sea route, where they attempt to reach Libya and then onwards via boats,” Jabbar said.

A difficulty in attempting to stop people from undertaking such a dangerous journey is that it is a “crime of consent”, he said.

“Traffickers have deployed this new tactic where they get legitimate documentation for those wishing to travel,” he explained. “How do you stop somebody who has a valid passport and visa? It then becomes a legal issue of stopping somebody’s right of movement.”

Hopelessness

Kashmiri, who lost his cousin and nephew, said that although the tragedy has saddened him, he still understands why his family members risked their lives trying to migrate to Europe.

“It is the hopelessness of this place which drives them to leave,” the 34-year-old said.

Pakistan is mired in an unprecedented economic crisis, with backbreaking inflation making food a luxury for millions of people. With high unemployment and no end in sight to the economic woes, Pakistanis have no choice but to head abroad for a better future.

“When a person decides to take this step, despite knowing all the risks involved, imagine yourself what motivates them to take this dangerous journey,” Kashmiri said.

“You must be incredibly brave to even think of doing this.”