The bodies of the victims who lost their lives at sea, 80 km southwest of Pylos on June 13-14 have been transferred to Schisto cemetery. At least 78 dead and hundreds remain missing. So far, 104 people have been rescued, while the search for survivors continues.

But critical questions remain about the Hellenic Coast Guard’s mishandling of what has become the deadliest shipwreck recorded in the Mediterranean in recent years.

The same is true regarding the responsibilities of Greece and Europe, whose policies have forced asylum seekers to opt for the deadly Calabria sea route, which bypasses Greece (for obvious reasons), and prohibits them from establishing legal and safe routes.

“Refusal to receive assistance”

In the briefings and timeline of the events leading up to the tragedy, the Hellenic Coast Guard attributes the failure to rescue the migrants before the fishing trawler sank, to the vessel’s repeated “refusal to receive assistance” during their communications.

The Hellenic Coast Guard became aware of the vessel in the early morning hours of Tuesday, June 13, and was, according to its own log, in contact with the vessel from as early as 14:00 local time. But no rescue action was undertaken, because “the trawler did not request any assistance from the Coast Guard or Greece,” the Hellenic Coast Guard reported.

The same communication was repeated at 18:00: “Repeatedly the fishing trawler was asked by the merchant ship if it required additional assistance, if it was in danger, or if it wanted anything else from Greece. They replied, “we want nothing more than to continue to Italy’.”

But does this absolve the Coast Guard of responsibility?

International law experts as well as former and active members of the Hellenic Coast Guard question the legal and humanitarian basis of this argument, even if there was indeed a “refusal of assistance”. And they point out to Solomon that the rescue operation should have begun as soon as the fishing trawler was detected, for the following reasons, among others:

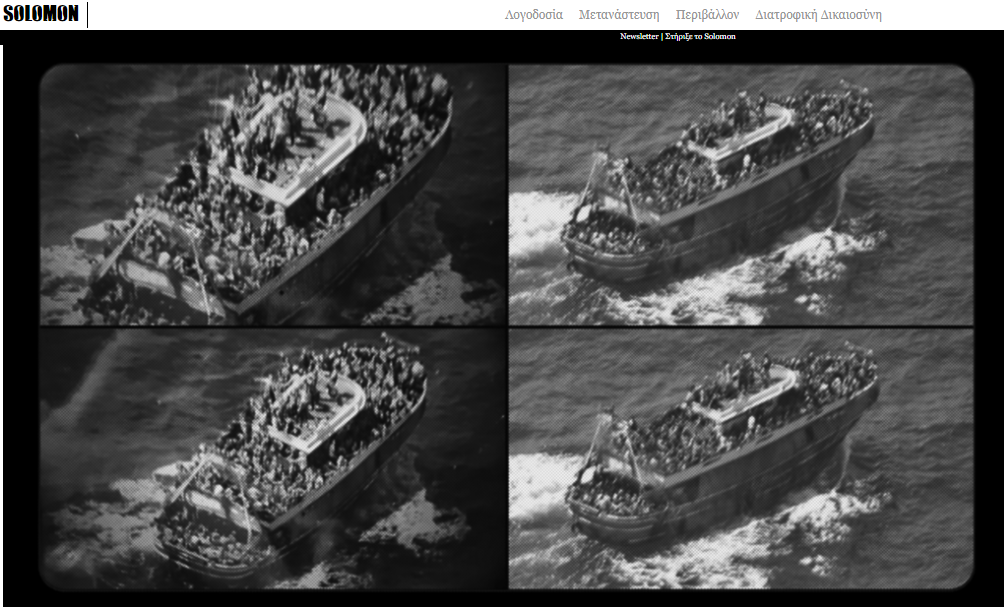

- The vessel was obviously overloaded and unseaworthy, with the lives of the people on board (who did not even have life-saving equipment) in constant danger.

- Accepting a denial of rescue or other intervention by the Hellenic Coast Guard would be appropriate only if the vessel carried a state flag, had proper documents, had a proper captain and was safe. However, none of these scenarios applies in the case of this particular fishing trawler.

- Hellenic Coast Guard officials had to objectively assess the situation and take necessary action regardless of how the passengers of the fishing trawler −or, to be precise, whoever the Hellenic Coast Guard was in contact with− assessed their own situation.

- The fishing trawler was undoubtedly in a state of distress that mandated its rescue from the moment the Hellenic Coast Guard received the SOS call via Alarm Phone, which was transmitted to the group by the passengers on board. This SOS call is not mentioned anywhere in the Hellenic Coast Guard’s communications.

Proof the Hellenic Coast Guard was aware that the vessel was in distress

In its own chronology of events, Watch the Med – Alarm Phone reports that it contacted the authorities at 17:53 local time in Greece.

The email to the authorities indicates the coordinates of the overloaded fishing trawler. It states that there are 750 people on board, including women and children, and includes a telephone number to contact the passengers directly.

The email reads: “They are urgently asking for help”.

The email, indicating that a vessel is in distress, was sent to the Hellenic Coast Guard, Hellenic Police HQ, to the Ministry of Citizen Protection, as well as to the Coast Guard in Kalamata.

The email was also sent to the UNCHR in Greece and Turkey, to NATO, as well as to Greece’s Ombudsman.

Listen to Solomon’s exclusive interview with Maro, from Alarm Phone:

Solomon contacted the Hellenic Coast Guard and asked detailed questions: Why wasn’t a rescue operation launched when they received the migrants’ distress call via Alarm Phone? Given the circumstances, does a “refusal of assistance” absolve the Coast Guard of responsibility? Why didn’t the Coast Guard at least carry out a simple inspection of the vessel (for security and identification purposes) since it was not flying any flag? Why was the operation launched only after the vessel sank?

A spokesman for the Coast Guard did not answer our specific questions but instead referred to the Coast Guard’s press release.

Solomon also contacted UNHCR, which confirmed receipt of the email.

“Our office was indeed notified yesterday (ed. note: 13/06) afternoon in correspondence received from Watch the Med – Alarm Phone, which referred to a vessel in distress southwest of the Peloponnese with a large number of passengers. We immediately informed the competent Greek authorities requesting urgent information about the coordination of a search and rescue operation to bring the people to safety”.

In an email seen by Solomon, Frontex responded to Alarm Phone’s message, stating: “Please be informed that Frontex has immediately relayed the message to the Greek authorities”.

“Duty to rescue, not stand by and watch”

The Hellenic Coast Guard had to treat the incident as a vessel in distress from the very first moment and take all measures to rescue the people on board, explains Nora Markard, Professor of International Public Law and International Human Rights at the University of Münster.

“As soon as the distress call was received via Alarm Phone, there was clearly distress. But when a ship is so evidently overloaded, it is in distress as soon as it leaves port, because it is unseaworthy. Even if the ship is still moving. And when there is distress, there is a duty to rescue, not to stand by and watch.”

International law defines distress as a situation where there is a reasonable certainty that a vessel or a person is threatened by grave and imminent danger and requires immediate assistance.

“That requires an objective assessment. If a captain completely misjudges the situation and says the ship is fine, the ship is still in distress if the passengers are in grave danger by the condition of the ship,” Dr. Markard explains.

International law unambiguously states that, on receiving information “from any source” that persons are in distress at sea, the master of a ship that is in a position to render assistance must “proceed with all speed to their assistance”.

In this particular case, the fishing trawler was not flying a flag, so the incident does not even fall under the category of respect for the sovereignty of the flag state.

“When a ship doesn’t fly a flag at all, as it appears to be the case here, the law of the sea gives other states a right to visit the ship. This includes the right to board the ship to check it out,” says Markard.

Apart from the distress call itself, the Hellenic Coast Guard, therefore, had the additional authority to examine the situation.

“All ships and authorities alerted of the distress have an obligation to rescue, even if the ship in distress is not in their territorial waters but at high sea. Search and rescue zones often include waters that belong to the high sea,” explains Markard.

“If the distress occurs in a state’s search and rescue zone, that state also has an obligation to coordinate the rescue. For example, it can requisition merchant ships to render assistance.”

Coast Guard officer: “This was the definition of a vessel in distress”

A former senior officer of the Hellenic Coast Guard with extensive experience seconds this and raises additional questions.

Speaking to Solomon on condition of anonymity, he explained that the vessel was manifestly unseaworthy and the people on board in danger. Even a refusal to accept assistance was not a reason to leave it to its fate.

The same official also points out there were delays in the Coast Guard’s response (“valuable time was lost”) and an inadequate rescue response. He confirmed that refusal of assistance would only be acceptable in the case of a legal, documented, seaworthy, and flagged vessel. “This was the definition of a vessel in distress”.

Similar statements regarding the claims of the Hellenic Coast Guard were made by retired admiral of the Coast Guard and international expert, Nikos Spanos, to Greece’s public broadcaster ERT:

“It’s like saying I can just watch you drown and do nothing. We don’t ask the crew on a boat in distress if they need help. They absolutely need help, from the moment the boat is adrift.”