First Published on Wearesolomon

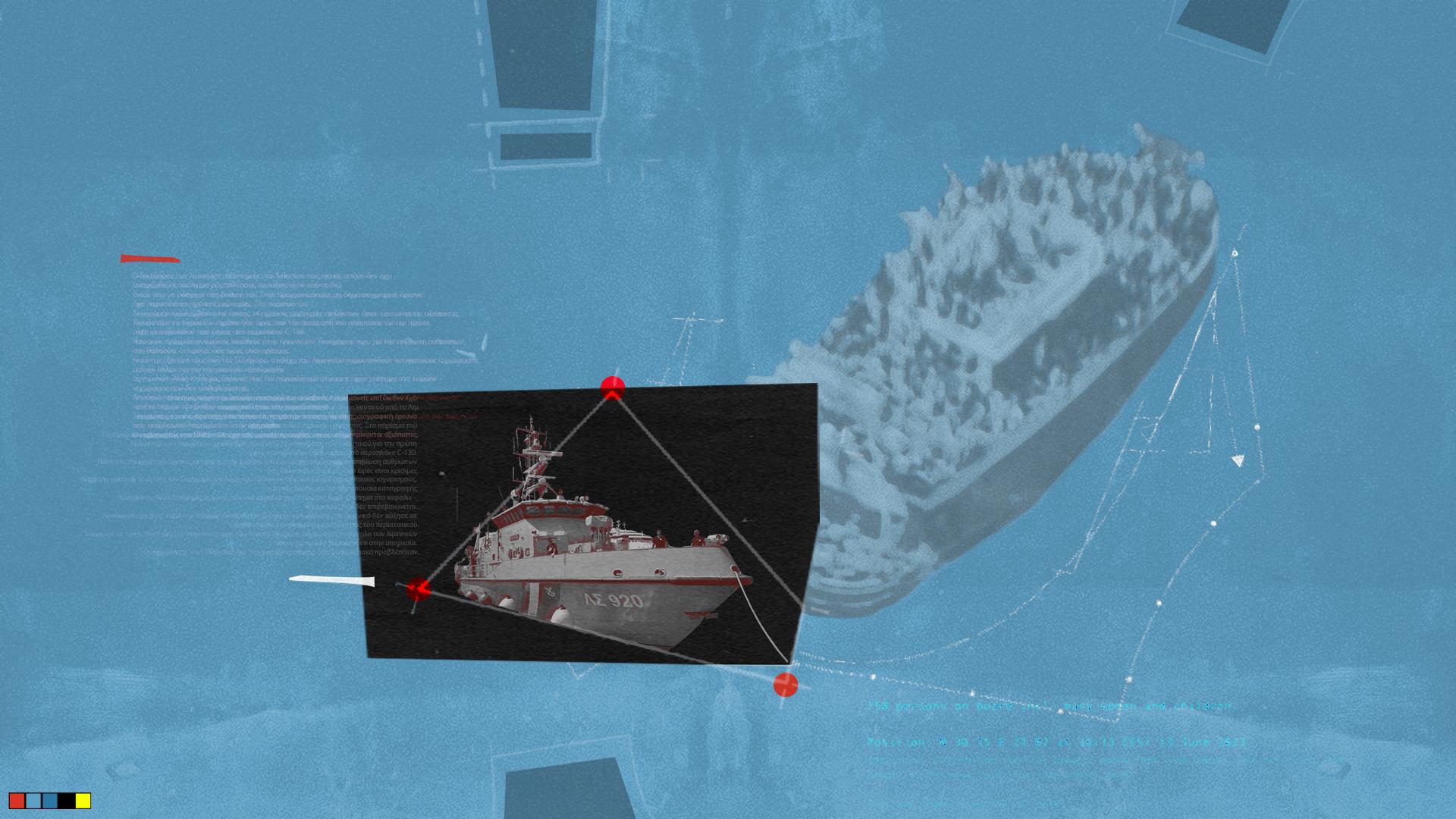

The Hellenic Coast Guard has faced unprecedented scrutiny since June 2023, when a fishing trawler overloaded with migrants capsized and sank off the coast of Pylos, killing more than 600 people. Thirteen Coast Guard officers–the captain and crew of patrol vessel PPLS-920, the only ship on the scene when the boat went down–now face criminal charges. In an exclusive interview with Solomon, their lawyer presented the officers’ defense. Their version of events is juxtaposed against the findings of the Greek Ombudsman, whose confidential report—obtained by Solomon—challenges several of their claims and notes shortcomings in Coast Guard leadership on the night of June 14, 2023.

“Ohhhhh.” The groan, recorded as members of the Hellenic Coast Guard crew of patrol vessel PPLS-920 pulled lifeless bodies from the sea, could be considered the defining sound of the Pylos shipwreck — the deadliest in modern Greek history, with more than 600 people lost.

The haunting cry appears in the Greek Ombudsman’s report, along with other audio evidence published here for the first time. The report itself has never been released, as it forms part of the case file.

Just after 2 a.m. on June 14, the fishing trawler that later came to be known as the Adriana sank southwest of Pylos. It had set out from Libya for Italy carrying, by official estimates, 750 men, women and children. In Piraeus, Coast Guard headquarters was informed that the sole vessel dispatched to the scene before the sinking, the PPLS-920, carried only two body bags.

A few hours later, shortly before 6 a.m., one of the senior watch officers on duty that night at the Joint Rescue Coordination Center (JRCC), Lieutenant captain Georgios Giotas, issued an order that laid bare the scale of unpreparedness: “Bodies stacked up, we have no other choice. Spread out a blanket at the stern.”

Elsewhere in the report, the same officer justifies Greece’s refusal to seek help from other rescue centers or from the European Border and Coast Guard Agency, known as Frontex. “We are self-sufficient, we don’t need assistance,” the report quotes him saying. “We are one of the best Centers in the world.”

By the end of that night, hundreds of lives had been lost. Only 104 people were saved.

Contradictions and leadership responsibility

By February 2025, Greece’s Ombudsman had completed a months-long investigation into the Pylos shipwreck. The confidential report, obtained by Solomon, pointed to “a series of serious and culpable omissions in the search-and-rescue duties by senior Coast Guard officers.”

The report followed the Coast Guard leadership’s refusal to launch an internal inquiry. Instead, the independent authority opened its own probe and uncovered failures that, it said, go all the way to the top command.

In May 2025, prosecutors brought felony charges against 17 Coast Guard officers. They include all 13 crew members of PPLS-920, accused of causing the shipwreck and of failing to provide assistance.

When Solomon met in June with their lawyer, Thrasivoulos Kontaxis, at his office in Athens, he insisted the officers had committed no crime, maintaining they were simply following orders from headquarters.

Through his interview with Solomon (the full transcript is available here), the crew’s version of what happened that night is presented for the first time. Placed side by side with the Ombudsman’s extensive report, to which Solomon gained access, it reveals eight key points where the defense narrative collides with documented findings.

- Following orders. The crew members insist they were carrying out instructions from the rescue coordination center and committed no criminal act.

- “Coincidences” and “malfunctions.” The Ombudsman’s report refers to a series of “coincidences” and “malfunctions” that heightened concerns about a possible cover-up. All communication with the trawler before it sank was conducted, “by mistake,” on the only analog line at the coordination center — the sole line not recorded, in violation of rules requiring round-the-clock documentation. The cameras on vessel PPLS-920 were also “out of order.” According to the report, they broke down almost immediately after the vessel was triumphantly delivered in 2021, despite a €55.4 million price tag for four ships.

- Sent “blind.” Structural flaws inside the Coast Guard meant that vessel PPLS-920 arrived at the Adriana without being briefed on crucial information: aerial footage, photographs and reports that passengers were already unconscious or dead.

- Disputed towing. Kontaxis told Solomon that no survivor has testified about a towing attempt. Yet independent journalistic investigations have documented such claims, and the Ombudsman’s report itself includes survivor accounts describing a tow.

- Delays in rescue. Nearly two hours passed after the trawler’s capsize before the first flares were dropped by a C-130 aircraft. The Ombudsman stressed that the first two hours are critical for survival at sea.

- Contradictory testimony. Officers gave conflicting accounts, including one senior official who claimed that “most of the dead had head injuries” and therefore could not abandon ship in time — an assertion not supported by autopsy reports.

- Failure to escalate. Despite timely warnings, including from the captain of vessel PPLS-920 himself, the Coast Guard never raised the incident to a higher risk level, as protocols required, until after the trawler had already sunk.

- Still on duty. According to Kontaxis, all of the officers he represents remain in active service.

The choice of vessel PPLS-920

Throughout the incident, all orders were issued from the coordination center, specifically by the two watch supervisors, who testified that they acted “with the approval of the entire chain of command.”

Rear admiral Tryfon Kontizas (then deputy chief of the Coast Guard and now its head) testified that the then–Coast Guard chief, Vice admiral Georgios Alexandrakis, had also called the secretary-general of the Migration Ministry to inform him of “the presence of this vessel and the large number of migrants” and to instruct him to be prepared in the Peloponnese and the Ionian islands– nearby areas where survivors might be brought or where operations might unfold.

In the same phone call, Alexandrakis reportedly ordered the port of Kalamata to be readied. Yet for more than 15 hours, the Coast Guard monitored the Adriana without ever issuing a rescue order.

The vessel chosen for the mission, patrol boat PPLS-920, was deemed “the most suitable and appropriate,” even though it could carry only 36 people and was equipped with just 43 lifejackets. Both the Ombudsman’s report and Kontaxis himself admitted it was manifestly inadequate for a mass rescue.

Patrol vessel PPLS-920 left Souda port in Crete at 3 p.m. and reached the area south of Pylos before 11 p.m., after nearly eight hours at sea. Why it took so long remains unclear. The distance was roughly 160 nautical miles, and with a service speed exceeding 32 knots, the journey should have taken about five hours, according to the Ombudsman’s report.

The Ombudsman’s report criticized the decision to send vessel PPLS-920, describing it as “substantially inferior in rescue capacity” compared with nearby tankers which the Coast Guard had instead ordered to leave the area.

The report also noted that the Coast Guard could have requested a Navy vessel with medical personnel, or deployed modern rescue boats such as the Aigaion Pelagos, stationed at Gytheio, a port town on the southeastern Peloponnese, not far from the site of the shipwreck.

Sent “in the dark”

The Ombudsman’s report highlights another critical flaw, underscoring the Coast Guard’s organizational dysfunction: vessel PPLS-920 and its captain were dispatched essentially “in the dark.”

After hours at sea, the ship arrived on scene without its captain having been briefed on key facts. He had, according to the report, not been told:

- of information received from the Italian coordination center in Rome about the number of migrants and the possibility of deaths on board;

- of subsequent reports that some passengers appeared unconscious;

- of Frontex aerial surveillance noting the number of people on deck and possibly below, and the lack of life-saving equipment;

- nor was he even shown the photographs already in the Coast Guard’s possession.

The omission is confirmed by a senior watch office on duty at the coordination center, who told the Ombudsman: “We gave him only basic information: the trawler’s position, the area, that it had a large number of people on board, and that they hadn’t requested assistance. We told him to go there in order to verify what was happening and whether there was indeed a risk.”

But the captain, Lieutenant commander Miltiadis Zouridakis, testified otherwise: “No, I was not given such information. The only thing they told me was to go to the location, where there was a vessel carrying a large number of migrants.”

Vice Admiral Alexandrakis, the Coast Guard’s chief at the time, said he had spoken with Zouridakis before departure, but described it as a short, formal conversation: “I wished them a good journey and he confirmed he had taken on water and provisions.”

The “blindness” of vessel PPLS-920

More than two years after the Pylos shipwreck, one central issue remains unresolved: the lack of audio-visual material to establish what exactly caused the disaster.

In a joint investigation by Solomon, the Guardian, Forensis and ARD, it was revealed that the European Border and Coast Guard Agency Frontex had already deemed it essential for Greek Coast Guard vessels to visually record their operations, after repeated and confirmed reports of human rights violations at sea.

Patrol vessel PPLS-920, one of the newest and most advanced ships in the Greek fleet, was delivered with great fanfare in 2021. Built in Italy at a cost of €55.4 million for four identical boats, the ships were designed to meet specifications set by the Coast Guard itself.

Yet on the night of June 14, the PPLS-920’s state-of-the-art recording system was not working. The Ombudsman’s report confirms what the captain had long complained of: that the cameras had broken down almost immediately after the vessel entered service, and that his repeated internal reports went unanswered.

“A year and a half before the incident – he filed at least three reports” lawyer Thrasivoulos Kontaxis told Solomon.“Everyone was aware.” When asked if the leadership knew the vessel would be dispatched without functioning cameras, Kontaxis said: “That is a logical conclusion… Everyone was informed [by those reports].”

The Ombudsman’s examination backs up that claim, documenting that captain Zouridakis had formally warned of failures in the vessel’s recording system.

The Ombudsman’s report raises three central questions:

- How could the cameras of such an expensive and modern vessel fail almost immediately after delivery?

- If they had indeed failed, why were they not repaired for nearly two years?

- And how is it that, just a month and a half after the Adriana disaster, the Coast Guard informed the Ombudsman that the system was once again operational?

The “black hole” of communications

The Ombudsman’s report identifies another critical gap: missing communications from the Coast Guard’s Joint Rescue Coordination Center during the most decisive hours of the disaster.

It documents “obvious gaps” in the official records, most notably between 11:34 p.m. on June 13 and 2:22 a.m. on June 14 — the period covering the patrol vessel’s approach to the Adriana and the trawler’s sinking.

No conversations with the fishing boat were recorded. Coast Guard officials said this was the result of a “technical issue”: out of eight available lines at the coordination center, seven were digital and automatically recorded, but officers had connected through the sole analog line, which was not.

Crew members later claimed they had used that line by mistake the first time and simply kept using it. The Ombudsman called that explanation insufficient, particularly since the Coast Guard’s own leadership had explicitly ordered that all communications be recorded at all times.

The report also notes that conversations between the coordination center and patrol vessel PPLS-920 are absent from the record for nearly an hour after the Adriana capsized at 2:06 a.m., even though the Coast Guard logbook shows the patrol vessel was on site until 3:06 a.m.

Kontaxis, the crew’s lawyer, acknowledged in his interview with Solomon that the captain also relied on his personal cell phone to communicate with headquarters when the official system did not connect. He conceded that the absence of proper recordings deprived investigators of crucial evidence.

The Ombudsman concluded that the lack of communications data has obstructed efforts to fully reconstruct what happened that night, while also intensifying suspicions of a possible cover-up: “How great a coincidence can it be,” the report asked, “that every exchange with the trawler and the captain of vessel PPLS-920 up to the moment of the sinking went unrecorded?”

Disputed towing attempt

One of the most contested questions in the Pylos case is whether the Coast Guard tried to tow the Adriana before it capsized. Survivors have repeatedly alleged that a towing maneuver caused the trawler to sink.

The Coast Guard initially denied any attempt at towing. Later, officials admitted that a line had been attached but insisted it was only to stabilize the vessels and enable communication.

Kontaxis, representing the crew of vessel PPLS-920, told Solomon that no survivor has testified that a towing attempt took place. He argued that the patrol vessel lacked the technical capacity to tow a ship of the Adriana’s size.

But the Ombudsman’s report cites survivor accounts that describe the capsizing as the direct result of a tow. It also points to a technical expert’s assessment that vessel PPLS-920’s power was more than sufficient to pull the trawler off balance.

At the center of the dispute is the “blue rope,” documented in previous reporting by Solomon, Forensis, the Guardian and ARD. The Coast Guard has said the rope was a mooring line, not designed for towing, and was used only to keep distance between the two vessels. Survivors, however, told investigators they saw it used to pull the Adriana before it flipped

A delayed rescue

The final stage of the tragedy, the rescue effort itself, was also riddled with failures, according to the Ombudsman.

The Adriana’s engine stalled for the last time around 1:35 a.m. on June 14. Less than half an hour later, at 2:06 a.m., the trawler capsized and sank. But the rescue coordination center did not issue a Mayday distress call until that very moment — and records from the luxury yacht Mayan Queen IV, the first vessel to arrive on the scene, show it received the Mayday only at 2:30 a.m.

The Ombudsman described the delay as “extremely critical,” noting that every minute mattered for passengers who had no life vests and were already exhausted and panicked.

The Coast Guard’s capacity to save lives was minimal. Vessel PPLS-920, designed to carry just 36 people and equipped with 43 life vests, rescued only about 50 survivors in the first hour after the sinking. The Mayan Queen IV arrived nearly an hour later, at 2:55 a.m., and took on dozens more.

Other assets were deployed only after the Adriana was already underwater. A Super Puma helicopter, a medium-life search-and-rescue aircraft operated by the hellenic air force, was ordered to take off at 3:31 a.m. to evacuate the severely injured. A C-130 aircraft began dropping illumination flares at 3:52 a.m.

As the Ombudsman noted, for people in the water, the first two hours are critical for survival. Even the slighter delay, the report warned, was “capable of dramatically reducing the chances of survival for those in the water.”

An obligation to protect life

Throughout his interview with Solomon, lawyer Thrasivoulos Kontaxis repeated a central defense: the crew of vessel PPLS-920 did nothing wrong.

“They were following orders,” he concurred when asked. The captain, Lt. Cmdr. Zouridakis, “did not do, or omit to do, anything. They told him: “go, approach, check.” He replied: “I’m checking; they don’t want [assistance]; I’m throwing the rope to stay in coordination with them; I’m removing the rope.” They told him: “since they don’t want [help], stay and wait.’”

Kontaxis argued that Coast Guard officers could not have forcibly evacuated the migrants before the trawler sank. “If people refuse… you cannot forcibly transfer them aboard,” he told Solomon. “Legally, you cannot carry out [a rescue] by force.”

The Ombudsman’s report rejected that reasoning, reminding the Coast Guard of a basic obligation: “The duty of the state is not only to refrain from taking life, but to protect it — through the real application of search-and-rescue rules.”

Despite the felony indictments, Kontaxis said all 13 officers he represents remain in active service. The captain of vessel PPLS-920 has since been promoted, in line with standard career progression practices.