A lot has been written about the denial of rescue, negligence and life-threatening actions of the Hellenic Coast Guard that constituted the state crime of Pylos. More than 600 people were drowned due to the direct actions and omissions of the responsible agents of the Greek state. The shipwreck of Pylos is one of the deadliest in the contemporary history of the Mediterranean, and the deadliest incident, which was directly caused by the actions of a state actor, since WW2 in Europe in time of “peace”. While the Greek state’s agencies that are responsible must be held accountable, European authorities and in particular Frontex’s involvement in this state crime must also be called into question and held responsible for their actions and omissions.

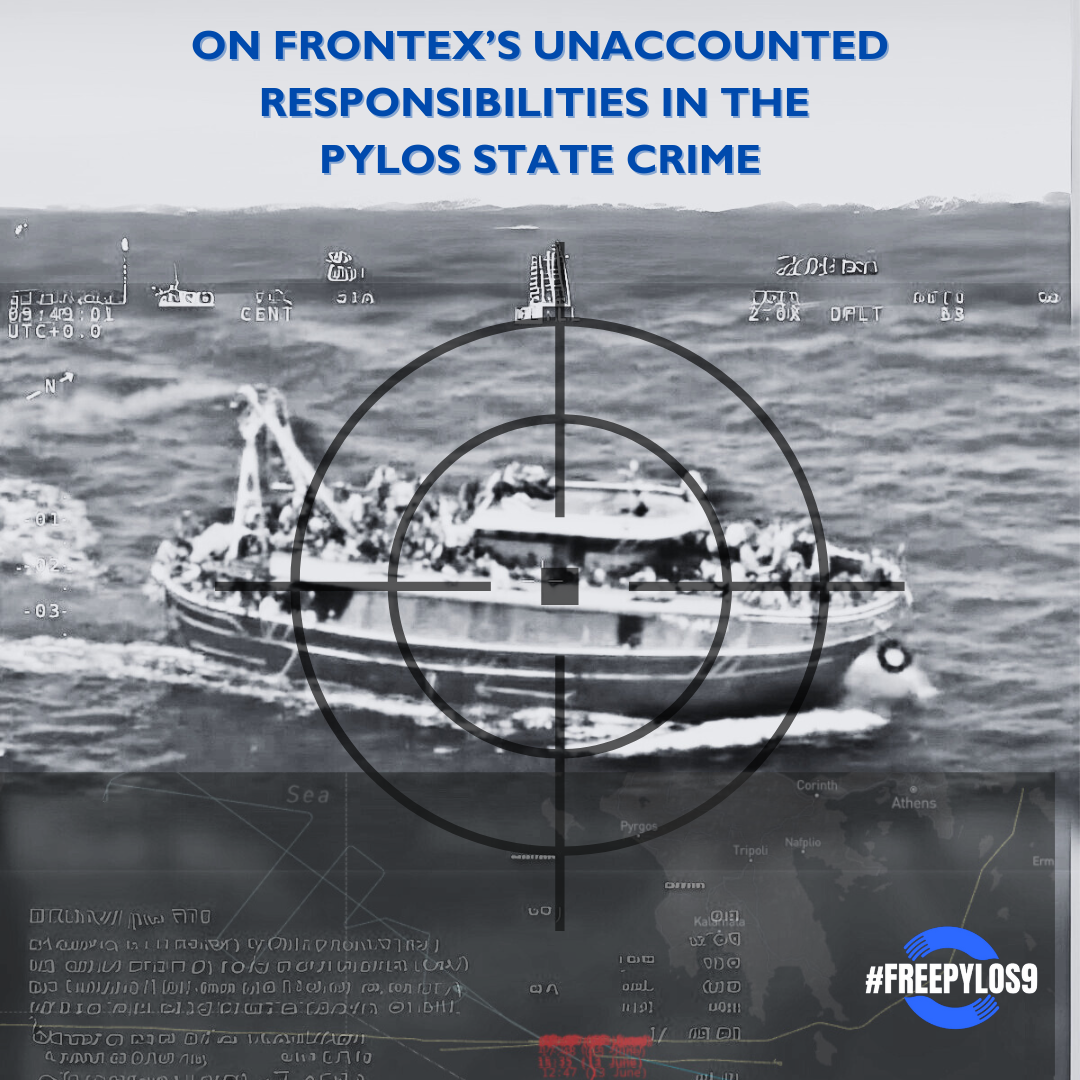

Following the shipwreck, Frontex attempted to distance itself from the actions of the Hellenic Coast Guard (HCG), (a) by asserting the exclusive responsibilities of the Greek authorities for the conduct of any Search and Rescue (SAR) operation in the Greek SAR zone, and (b) by justifying the actions of Frontex during the incident. Frontex, together with the Joint Rescue Coordination Centre of Piraeus, of Malta, and the European Union Naval Force Operation in the Mediterranean were initially informed of the existence of a boat in distress on 13 June at 08:01 a.m. (UTC) by the Italian Maritime Rescue Coordination Centre. Frontex provided its surveillance aircraft Eagle 1, which was deployed under the Joint Operation Themis in the area, to spot the Al Mutawakkil trawler (misidentified and referred to as Adriana by the international press), which took place at 09:47 a.m. (UTC).

The footage of the Al Mutawakkil recorded by Frontex itself was clear: the vessel was unseaworthy; it was heavily overcrowded; it was sailing under no state’s flag; and there was no life-saving equipment on board. This, together with the information that had reached the Frontex headquarters in Warsaw about there being dead people on board (before the shipwreck), and that people on board had reached civil society organisations to ask for rescue, should have been enough to identify and report an undoubtful situation of acute distress. However, Frontex’s chain of operation decided not to handle this case as one of a vessel in distress and only provided the Greek Authorities with the footage of the Al Mutawakkil, thereby failing in its responsibility to issue a mayday relay. This chain of decisions, which as per an inquiry carried out by the European Ombudsman following the shipwreck, appears to be in line with Frontex’s operational guidelines,[1] questions the effectiveness of these guidelines and their compatibility with search and rescue obligations under international law. It also demonstrates a clear political stance to treat the migrants on board as though their lives are of secondary importance. It is obvious that if the ship in distress had been a cruise liner or a luxury yacht, a timely and safe rescue operation would have been launched. Such dehumanising distinctions between human lives have a long history and have led to many tragedies before and since the “Pylos Shipwreck”.

Frontex states that it attempted in two different moments to assist the Greek authorities by redirecting its aerial assets to the location but did not receive any response. Meanwhile Frontex had been informed repeatedly by civil organisations about the life–threatening tragic situation on board. Despite that, Frontex’s offer to reinforce the HCG’s efforts came a full 6.5 hours after the initial contact with the boat and despite the repeated alerts they had received; the offer of assistance was rejected by the HCG. However, the delay in response to the vessel in distress by the Greek authorities should have been sufficient justification for Frontex to intervene on the spot. The decision of the Greek authorities not to respond to the assistance offered by Frontex, does not relieve the agency from its own formal obligations to reassess the situation. To the contrary, these delays and lack of responsiveness of the HCG should reasonably have alerted the agency, all the more, that an increased intervention and scrutiny was needed. Especially since the footage recorded by Frontex itself and the information it received from other sources evinced the unseaworthy state of the vessel and the risks to the safety and lives of people on board.

The systematic unlawful practices of the HCG have long been documented: delaying and denying rescue, attacking and pushing back migrants’ boats; increasingly using weapons and killing people trying to cross the sea, without any respect for international and maritime law or for the protection of fundamental human rights and lives. Given this evidence of the HCG’s track record, Frontex should not have taken at face value the HCG’s explicit reinsurance that it would intervene and assume responsibility for search and rescue. Rather, Frontex should have reasonably doubted the effectiveness of the HCG’s efforts to assist people in distress, in this case those on board the Al Mutawakkil vessel. Frontex’s decisions (a) not to register the case as one of distress; (b) not to call for a mayday relay; and (c) to withdraw its assets away from the area, meant, in practice, that it allowed the Greek authorities to extensively delay their intervention and to carry out yet another illegal operation, like the systematic pushbacks and dangerous sea operations that happen from Greek to Turkish waters. This was not the first time that Frontex has done this, as identified in the report by the European Anti-Fraud Office (OLAF) on the misconduct of several individuals employed by the Agency in relation to Frontex operational activities in Greece in 2020.[2] Frontex often relocates its officers and assets away from locations where they would witness first-hand the Hellenic Coast Guard performing illegal pushbacks.

A lot more could be said about the evolution of the role of Frontex in border violence in Europe. It’s renaming as the ‘EuropeanBorder and Coast Guard Agency’ in 2016 highlights its transformation from an entity whose only role was to secure the external borders of the EU, into an agency that has Search and Rescue amongst its core objectives. However, rather than undertaking SAR, in practice Frontex acts as the uniformed, militarised body of Fortress Europe. Frontex did nothing to prevent more than 31,000 people dying or going missing in the waters of the Mediterranean since 2014[3]. The multiple reports that demonstrate misconduct and violations of human rights in Frontex operations,[4] to date, have had no impact, nor have policy recommendations for the alteration of its practices to respect human rights. Frontex continues to play a key role in the systematic and increasing criminalisation, dehumanisation, and endangerment of people on the move. The huge increase of the Frontex budget brings it to a sum of more than 1 billion euro;[5] Frontex expenditures are exclusively on surveillance and control assets rather than Search and Rescue equipment. Frontex is key to the border industrial complex, driven by the multi-billion arms and security industry, and justified through a political discourse that fuels fear and division, which has become dominant not only in parliaments dominated by the far–right, but also amongst European citizens.

A year has passed since the decision of the European Ombudsman, following the deadly shipwrecks near Pylos and Crotone. This decision called for needed changes in Frontex’s code of conduct when dealing with maritime emergencies and during its joint operations with member states. However, to date, there is no sign that any of these recommendations have been adopted by Frontex. Following the recent decision of the European Court of Human Rights which clearly identifies that illegal pushbacks are systematically being performed by the Greek authorities,[6] Frontex should immediately terminate its joint operations with the Greek state, in line with Article 46 of Regulation 2019/1896.

In addition, the ongoing criminal investigations of the Greek authorities for the events of the Pylos Shipwreck should also be expanded to identify any direct or indirect co-responsibility of the Frontex Officers involved in the chain of operations, including the ones responsible for coordinating joint operations. We demand the thorough investigation of the actions and responsibilities of all actors involved in the state crime near Pylos, to which Frontex was a party. All those responsible should be held accountable.

We call for justice for the survivors and for the memory of those who did not survive the deadly state crime!

#FreePylos9

12/03/2025

[1]https://www.ombudsman.europa.eu/en/decision/en/182665&sa=D&source=docs&ust=1741173471977085&usg=AOvVaw1XrJUy6XhCclysTjsr-Gqd

[2] https://fragdenstaat.de/dokumente/233972-olaf-final-report-on-frontex/

[3] https://missingmigrants.iom.int/region/mediterranean

[4] https://www.europarl.europa.eu/cmsdata/238156/14072021%20Final%20Report%20FSWG_en.pdf

[5]https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=OJ:C_202500847

[6]https://hudoc.echr.coe.int/app/conversion/pdf/?library=ECHR&id=003-8124877-11378031&filename=Judgment%20A.R.E.%20v.%20Greece%20-%20%E2%80%9CPushback%E2%80%9D%20of%20Turkish%20national%20to%20T%C3%BCrkiye%20without%20examining%20risks%20she%20faced%20on%20her%20return.pdf